Chapter 10 - Networking: Market Competition 1981-1983

10.20 The AT&T Settlement: January 1982

In February 1981, William F. Baxter became the new Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust for the newly elected Ronald Reagan Administration. He was a Stanford law professor, with strong ideals, and a considered view of economics and competition. On taking office his two superiors recused themselves from involvement in the AT&T anti-trust case for conflict of interest reasons. Baxter thus became the chief Justice Department official on the case – reporting to the White House. Baxter decided to handle the case personally and not be burdened with what had happened before him and the constraints implied. He saw the case as one of extending what the FCC had started – to separate from AT&T that best regulated, from that better controlled by the forces of market competition.12 On his first meeting with the chief counsel and negotiator for AT&T, Howard Trienans – who had came not from within AT&T, but an outside law firm, and was thus somewhat similarly unencumbered by past practices - Baxter terminated past negotiations, and stated his position: AT&T should divest the Operating Companies and go about its business competing with the Long Lines, Bell Labs, and WE. Period.

On September 3, 1981, Judge Vincent Biunno of the New Jersey District Court ruled that the FCC’s Computer Inquiry II Final Decision preventing AT&T from competing in unregulated markets, unless as separate subsidiaries, was a legal modification of the 1956 Consent Decree. AT&T immediately filed an appeal.

By December, AT&T, motivated to a decision by Congressional activity to pass communication legislation – legislation that might be much worse than Baxter’s offer – relented. A joint press statement was released on December 31 announcing talks that might lead to the “settlement of pending litigation.”13 Baxter then went to work securing Administration support for the agreement; support not to be presumed. On January 8, the Justice Department and AT&T, Baxter and Brown, signed a decree ending the antitrust suit.14 Then in an intricate series of legal maneuvers, the case was to be moved from the New Jersey District Court to Judge Greene’s court and the settlement would revise the 1956 Consent Decree and settle the case.15 Or it was suppose to be moved, only Judge Biunno accepted the agreement instead of referring it to Judge Greene, which meant it could be appealed and thus not final.

In both Houses of Congress legislation began emerging seeking to change the terms of the agreement to better assure that local telephone rates remained low and the principle of universal service remained intact. Concerned elected officials still saw long distance telephone service as a monopoly, a monopoly needing to be regulated, in part, so that subsidies could continue to flow from interstate to intrastate revenues, and thus help sustain low local rates. The Justice Department, AT&T, and now an angry Judge Greene, who saw his authority abused by the New Jersey court, all wanted their agreement to be made final and not complicated by legislative action. AT&T began a publicity campaign inciting public protest over legislation, which proved successful, and the three parties succeeded in having court authority transferred to Judge Greene’s court. Judge Greene then inserted ten modifications, all of which were accepted, and the settlement was finalized on August 24, 1982. One of the ten amendments to the agreement was that the Bell Operating Companies could provide customer premises equipment (CPE): they just couldn’t become manufacturers. They would have to buy CPE from competitive firms, including AT&T.

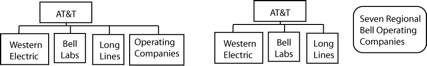

The dismembered AT&T had two parts. First, a succeeding AT&T, a corporation having the same name: AT&T, composed of Western Electric, Bell Laboratories and Long Lines. It had all of the manufacturing, most of the research and development, and the long distance telephone network. The other part of the dismembered AT&T was all the local telephone companies: to be organized into seven Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCs). The new AT&T continues to be of interest to this history. (See Exhibit 8.3 AT&T Reorganization January 1982).

Indicative of the business judgment of the day, Arthur D. Little executive Frederic G. Withington, remarked:

On the surface, AT&T appeared to give away the store. But a second, more studied look indicates that they really gained the store. In fact, you might ask if AT&T lost any power at all.

Exhibit 10.20.1 AT&T Reorganization January 1982

Before January 1982 After January 1984

- [12]:

Temin, p. 219. The reader is encouraged to read Temin for a far better reconstruction of this period.

- [13]:

Henck, p. 228

- [14]:

On the same day, the Justice Department withdrew its case against IBM. Baxter saw one way to introduce competition for IBM was to let AT&T compete in the computer market.

- [15]:

Temin, p. 275